A man pushes an Asian woman into the path of a subway. A man travels to New York City and opens fire in a crowded train after setting off smoke bombs. And the calm of a Saturday at a supermarket in Buffalo is shattered when a man opens fire and kills 10 people, injuring three in a predominantly Black neighborhood.

The incidents over the last several months have revived calls from officials denouncing hatred and racism spread online, but also a push to strengthen mental health programs in New York.

But advocates for people who are facing mental health challenges worry the rhetoric in the wake of the tragedies will both villify and criminalize vulnerable people.

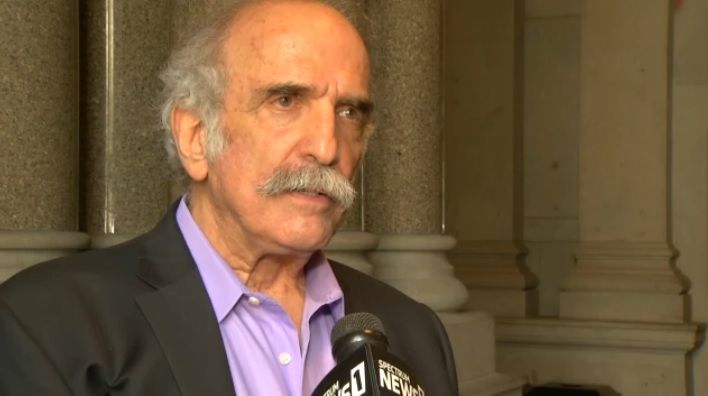

"When you hear about outrageous crimes like this with such horror, it's sometimes normal to say you'd have to be crazy to do that," said Harvey Rosenthal, CEO of the New York Association of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services and a longtime mental health advocate. "But we're not talking about mental illness. What we know here is racism is not a mental illness. Maybe he was being taught to hate, so I think we have to be very quick not to criminalize people with mental illness."

The alleged shooter in Buffalo is believed to have written a racist diatribe that decries the "replacement" of white people by immigrants of color. He was also known to police last year after allegedly threatening his high school.

New York lawmakers and Gov. Kathy Hochul this year have debated measures that would expand Kendra's Law in the state, a measure that requires people in a mental health crisis to receive treatment. Rosenthal had been sharply against the expansion.

But more broadly, he's concerned the focus on mental illness as a reason for heinous acts will hurt vulnerable people.

"That has been the story in Albany all session," he said. "We have vilified the mentally ill. We've heard it from both houses at times. It's really got to stop. The conflation of violence has been egregious, and villified an entire group."